The over use (and abuse) of historical analogies may seem innocent, but as the historian Linford D. Fisher points out, they are not harmless. The main problem is that “they dumb down our political discourse, cheapen the actual realities of the past, and rob us of the opportunity to genuinely understand and learn from the past.” This outcome is the result of “comparisons [that] are shallow and not rooted in any depth of meaningful knowledge of the past. They rely on caricatures and selective historical tidbits in a way that, indeed, just about anyone can be compared to anyone else.” In other words, they are very bad analogies.

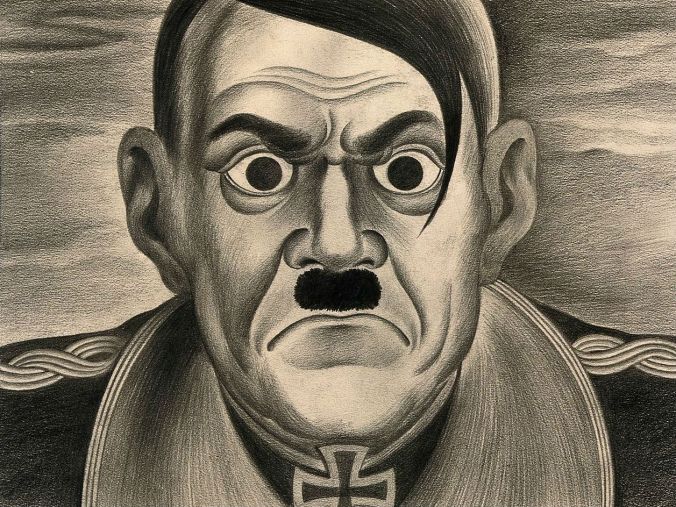

Some of these analogies are a product of ignorance, but too often they are trotted out to serve political ends. If your goal is to discredit Obama, then just keep calling him “Hitler,” “a fascist,” and/or “a communist” (the fact that this is incompatible with the other two is never considered). This kind of extreme rhetoric has been successful at turning a significant portion of the population against the president, making it easier for Congress to oppose him at every turn. Their effectiveness ensures that they’re not going anywhere anytime soon.

But there is hope. One way to combat against this abuse of history is through education. This is one reason why the humanities are particularly valuable. They provide the critical thinking skills needed to see through such crude analogies. And, of course, a broad and in-depth knowledge of history is also helpful.

Done correctly, historical analogies can be very useful. As Fisher notes, “history gives us perspective; it helps us gain a longer view of things. Through an understanding of the past we come to see trends over time, outcomes, causes, effects. We understand that stories and individual lives are embedded in larger processes. We learn of the boundless resilience of the human spirit, along with the depressing capacity for evil — even the banal variety — of humankind. The past warns us against cruelty, begs us to be compassionate, asks that we simply stop and look our fellow human beings in the eyes. All of us — grandstanding presidential candidates and partisan tweeting voters — could use a little more of this kind of history, not less.”

Read Fisher’s germane plea here: Your Hitler analogy is wrong, and other complaints from a history professor – Vox